There we were: me, my partner, and my mother, having breakfast in the Savoy Hotel in London before our river cruise, and the conversation drifted to Maurice Ravel‘s Boléro, as it so often does.

I recalled a painting by Canadian artist Anne Adams, Unraveling Boléro, inspired by this evocative orchestral piece. This painting represents the music as a series of rectangles, one per bar. Each rectangle is coloured according to the dominant note in the bar. The height of the rectangle corresponds to the volume of the music. Other embellishments correspond to the rhythm and the instrumentation. It’s rightly regarded as Adams’s masterwork.

The three of us at breakfast that day all do quilting, and Unraveling Boléro looked a lot like something that could be quilted. But copying someone’s art didn’t excite me. Mum suggested another well-known piece of classical music, something out of copyright. How about Edvard Grieg‘s In the Hall of the Mountain King, from the Peer Gynt suite?

Over the course of the cruise, I mulled over ideas for the quilt, and before too long, it had become a series of four quilts, one for each of the movements of Suite 1. Each of the movements had its own special challenges, as I was to discover.

Ground rules

I didn’t want to do a straight copy of Adams’s technique: some of the aspects of the painting wouldn’t translate well to fabric, and I guessed that a lot of the design decisions Adams made were rooted in her choice of Boléro, and would not be applicable in the context of another piece of music. With that in mind, the axioms for my quilts were:

Quilt axioms:

- One rectangle per bar.

- One colour per note.

- Adjacent bars in adjacent rectangles.

These axioms each proved to be clear, simple, and wrong.

Anitra’s Dance

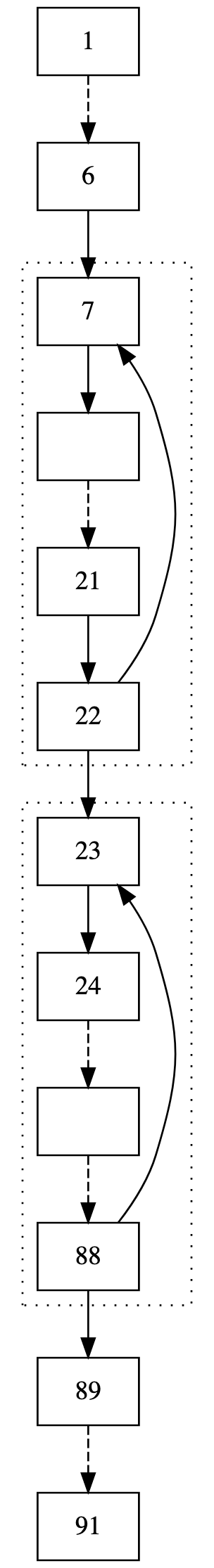

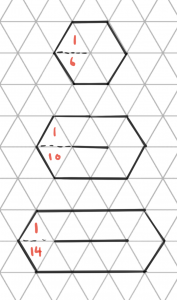

The third movement, Anitra’s Dance, was likely to be the most challenging movement: it is the only one of the four movements to have repeats, adding complexity. Bar 7 is preceded by bar 6, but also by bar 22. There is another repeat after bar 88, back to bar 23. Application of Axiom 3 (“Adjacent bars in adjacent rectangles”) constrains the arrangement of bars. It also forces the arrangement of rectangles into two dimensions: the left-to-right, top-to-bottom progression in Unraveling Boléro—just like a book—won’t work, because there is no scope for returning to an earlier bar without doubling back.

A bit of scribbling on paper made it clear that arranging the bars in a rectangular grid to satisfy Axiom 3 was possible but underconstrained. A new axiom was needed.

Quilt axioms:

- No empty space inside.

But arranging the bars compactly in a rectangular grid produces an inelegant mess. It was technically correct but not evocative of the music. It was tantalizingly almost symmetric but could never be, because the second repeat was not a multiple of four bars in length.

One of my axioms had to go. It turned out to be Axiom 1 (“One rectangle per bar”): rectangles were just too limiting.

Triangles

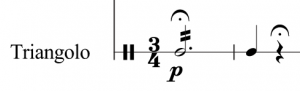

Anitra’s Dance is a waltz, in 3/4 time, for string ensemble and triangle. The pervasive three-ness of the movement took a painfully long time to dawn on me. I was blinkered by the rectangles of Unraveling Boléro, but other shapes can tessellate too.

Quilt axioms:

- One

rectangletessellating shape per bar.

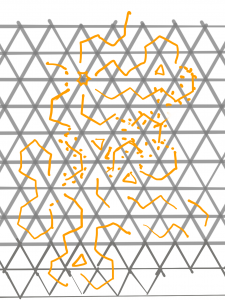

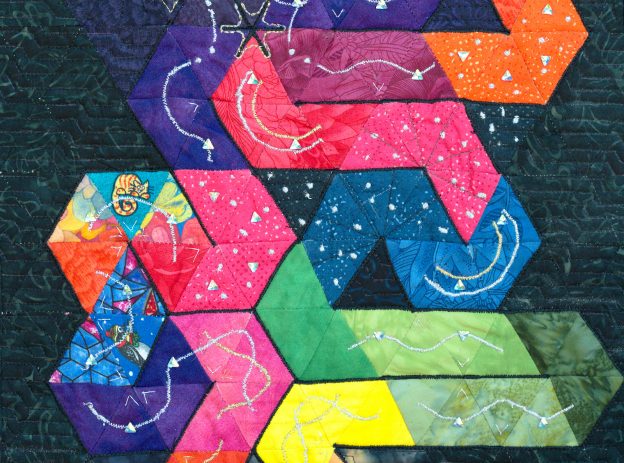

This turned out to be the right decision. With a triangular grid, you have to tack across it in a zigzag to get anywhere. The path naturally curls into bends, every four bars making an angular croissant. This brownian movement lent itself to the fluidity of Anitra’s Dance, which is, after all, a dance.

It was soon apparent that on a triangular grid it is not possible to lay out sixteen triangles in a continuous loop without leaving a hole in the middle, so another axiom had to be relaxed to satisfy the bar 7-to-22 repeat.

Quilt axioms:

NoNot much empty space inside.

This newfound freedom in laying out triangles for bars was tempered somewhat by the volume of the search space. While the bar 7-to-22 repeat could only be drawn a few ways, the 66 bars of the second, longer repeat could be organized in a myriad of ways, and drawing them was becoming tedious. How could I choose the best arrangement?

Protein folding

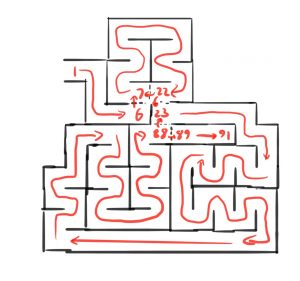

I made a model out of card and paper fasteners corresponding to the bars in the movement. I hoped that arranging this model on the table and manipulating the angles between segments would help me to explore the solution space while ensuring that the constraints imposed by the repeats were handled automatically.

It should not be a surprise to anyone who has spent time around protein folding that this was wishful thinking. In practice, the paper model was unwieldy and uncooperative. Keeping the angles between segments at 120º was a constant battle. It turned out to be quickest to sketch a potential layout on the Procreate app on an iPad, and verify it using the paper model.

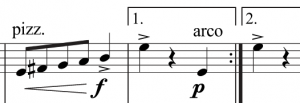

One benefit to using the paper model was that I could use different colours to represent the different themes and instrumentations in the music. In keeping with the idea of protein folding motif, I wanted to keep related parts of the music physically near each other. Specifically, in Anitra’s Dance, there are four lengths, each four bars long, which are dominated by pizzicato arpeggios. I wanted these lengths to be near each other. There is also a phrase from bars 42-45 in the key of D major, repeated immediately afterwards in bars 49-52 in the key of D minor, and I wanted these themes to be adjacent to each other, mirrored, but in opposite directions, as if the dance had taken an unexpected sinister turn.

Quilt axioms:

- Keep similar parts near each other.

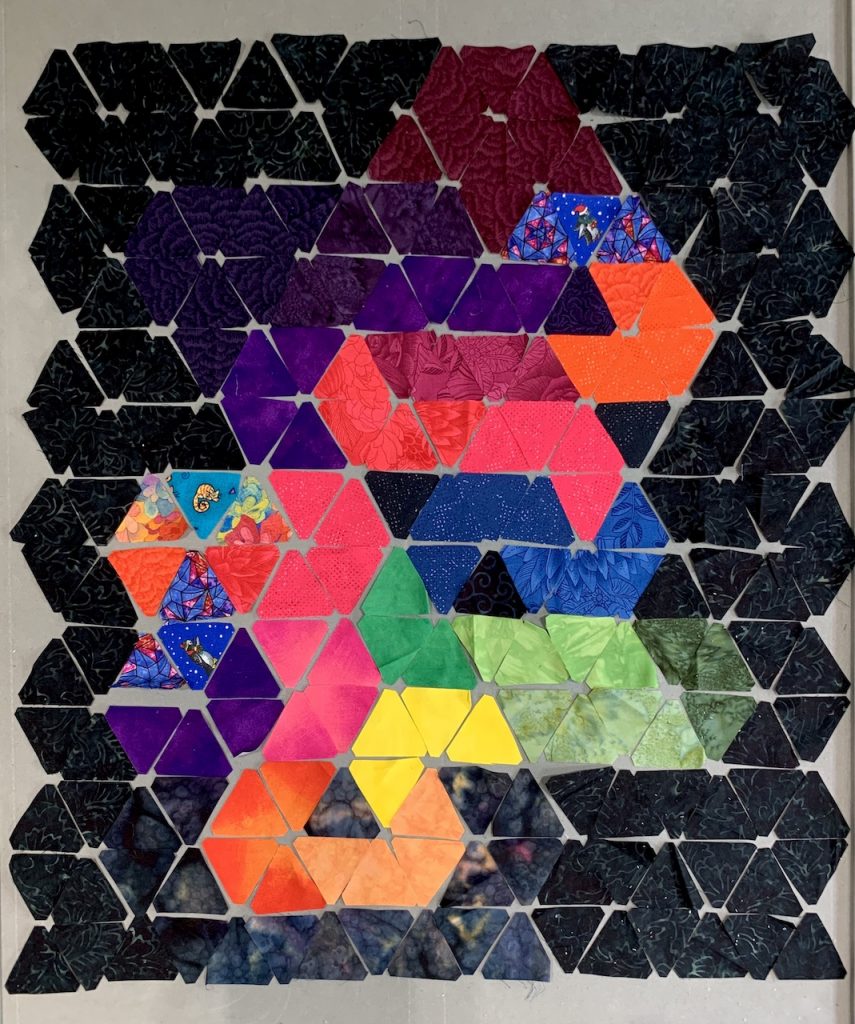

The arrangement that I settled on was able to satisfy these new axioms. It was a pleasing meander across the page, with a nexus at the upper left where the repeats meet up. There ended up being four triangular holes inside the shape.

Colour choices

Now that I had the shape of the quilt, it was time to choose fabrics to make the quilt from. One of the most opaque aspects of Adams’s Unraveling Boléro for me was the artist’s choice of colours for each rectangle. She stated that the colour corresponded to the most prominent note in that bar, but even if I follow the painting while listening to Boléro, I admit I still don’t know what colour corresponds to what note.

Boléro, written in 1928, is renowned for its rhythm full of triplet notes and for its rambling melody, not its harmonies. The first chord, C major, lasts for 326 bars! In contrast, Peer Gynt, written in 1875, is firmly of the Romantic era, and its harmonies are central. Perhaps the quilt should track harmonies and not notes.

Quilt axioms:

- One colour per

notechord.

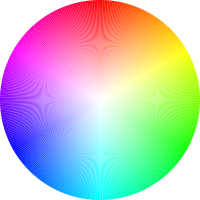

My first instinct was to assign colours to chords according to a colour wheel. There is an arrangement of chords in music theory where chords that are a perfect fifth apart appear next to each other. In equal temperament, the diagram overlaps at F♯ and G♭, producing a cyclic diagram known as the circle of fifths. It seemed natural to overlay these two diagrams on each other and just read the colours off it. But upon trying this, I wasn’t happy with the results. Grieg’s music doesn’t often walk around the circle of fifths, so the colours produced by naive application of the colour wheel were garish. It might be appropriate for a composition from the Baroque period, perhaps, but Romantic music such as Anitra’s Dance makes a lot of use of diminished chords, suspended fourths, suspended flat ninths, and minor sixths, and I wasn’t even sure how to pinpoint these more complex harmonies on the circle of fifths. So I abandoned the circle of fifths as a guide, and just chose colours that looked pleasing.

Synthesis

The Procreate app proved useful while assigning colours, because it has a command to apply a hue/saturation/brightness shift to a layer. Don’t like blue for the B major chord? Change the hue of the B major chord layer so that it’s red instead. By putting each chord on its own layer, I could ensure that all the (say) E major chords consistently used the same shade of (say) pink. I could also embellish the path with overlaid scribbles to represent the melody and instrumentation.

During the digital design, I made some choices that survived to the physical quilt:

- Quiet bits are darker than louder bits.

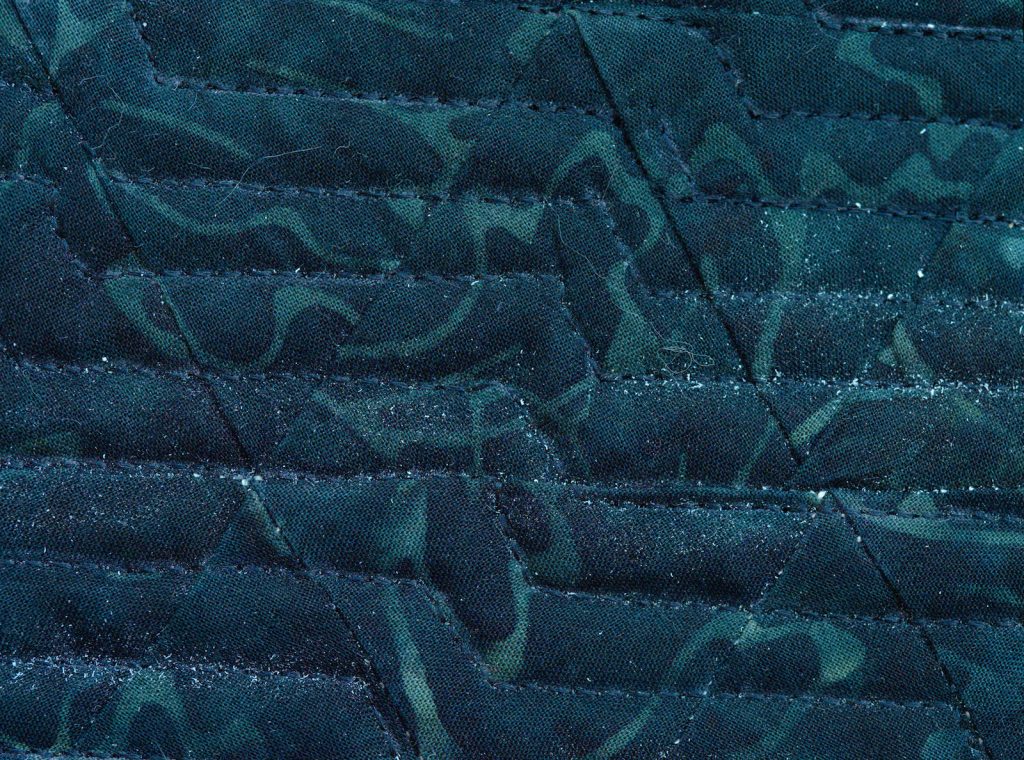

- Pizzicato feels dotty to me, and would be made of fabric with dots.

- Major and minor chords with the same tonic would have the same hue but the major chord would be more saturated, most obviously seen in the green D major and D minor phrases.

- Diminished seventh chords don’t really have a tonic, because C dim7 = E♭ dim7 = F♯ dim7 = A dim7. Similarly with augmented chords, not that this movement has any. These chords would not be a solid fabric colour but would use a pattern.

- The bars that have a triangle in them will be marked somehow.

Piecing the quilt

The digital design of the quilt didn’t always directly translate to fabric. This was during the 2020 lockdown in Melbourne, so the option to go browsing in quilt stores wasn’t available. Enter a new axiom.

Quilt axioms:

- Everything has to come from my fabric stash.

This actually wasn’t too big a restriction, but it does serve to explain some of the changes that took place in the physical quilt.

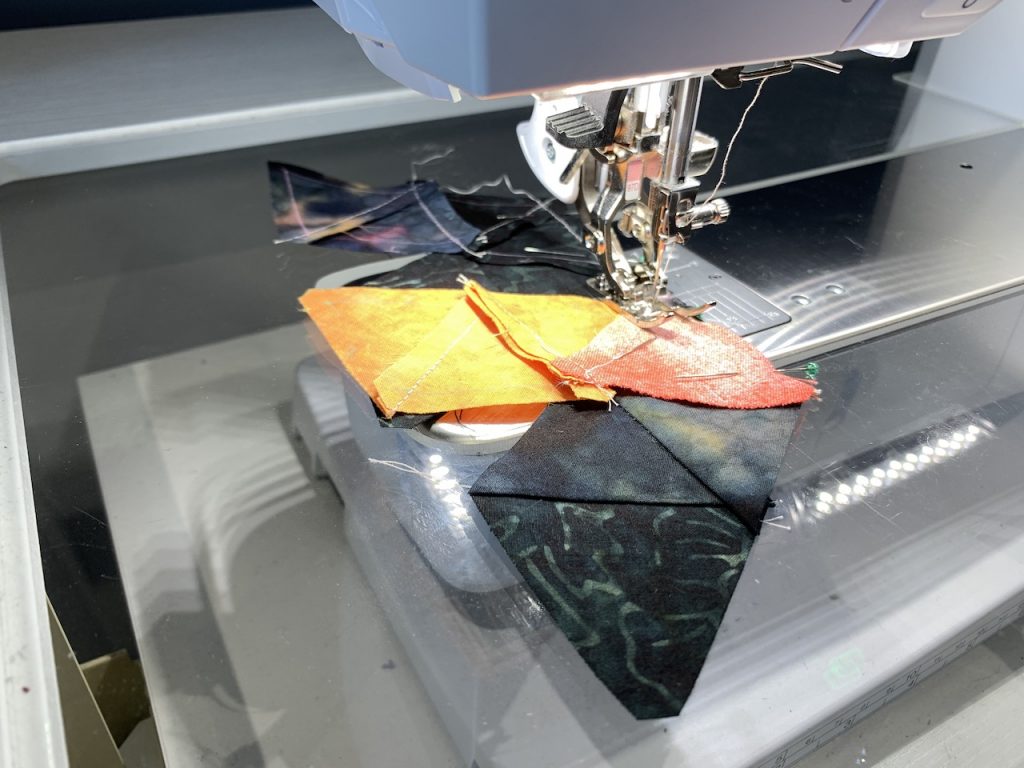

I pieced the quilt using traditional machine piecing. Each triangle is 1¾″ from corner to corner with an additional ¼″ seam allowance.

Quilting

I machine embroidered and quilted the quilt using Gütermann metallic thread, Gütermann invisible thread, and black rayon thread.

Finishing

The (geometric) triangles where (musical) triangles play are embellished with (iron on) rhinestone triangles. The finished quilt measures 44 cm × 51 cm (17″ × 20″).

This is part 1 in a series of four posts.

Leave a Reply